I’ve been collecting data on state legislative endorsements of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates. This is one lens to understand how party elites sort out who to support as the leader of their party in the single most important election in the country. Congressional and gubernatorial endorsements are being collected by FiveThirtyEight, and that’s important, too. But state legislators are more diverse, more free to make sincere choices, and there are just so darn many of them to help us analyze them.

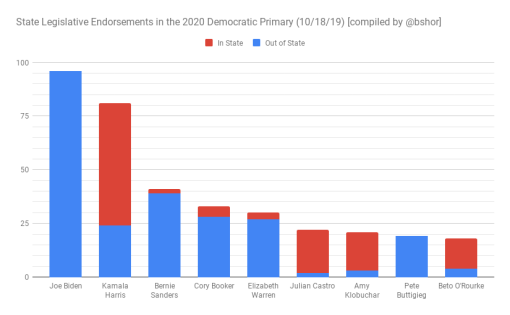

There are 3,465 Democratic state representatives and senators. Around 640 or around 18% of them have made an endorsement (up from 10% in October). At the same time, about 48% (up from 33% in October) of the early state (Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada) Democrats have made a choice, which makes sense, as the early states are where the campaigns are most furiously operating. For comparison, only 11% of the Super Tuesday (March 3, 2020) residing Democrats have made a choice. Note that I’m only counting endorsements of active candidates so Kamala Harris’ large number of California endorsements are no longer being counted (thus, in October 13% of Democrats had endorsed then-active candidates).

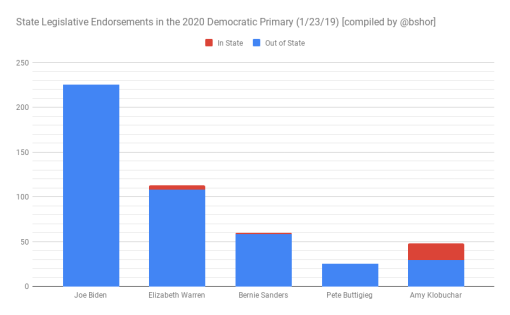

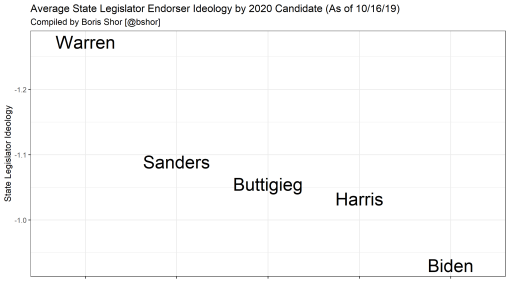

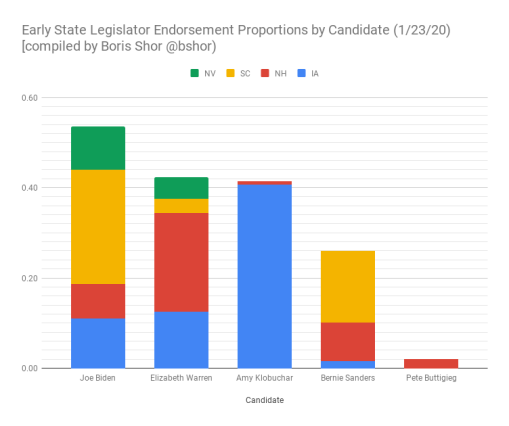

Let’s look at the endorsement race as a whole, which Joe Biden still leads by a substantial margin, which matches his still-strong poll numbers. Notably, Elizabeth Warren who had been in 5th place in October, now is in second place. Bernie Sanders has relatively few endorsements relative to his poll numbers, while Amy Klobuchar has relatively more endorsements relative to hers. Pete Buttigieg has very few in general.

Note also how, with the exception of Klobuchar, the top candidates get zero or near-zero support from home state legislators. Familiarity breed contempt?

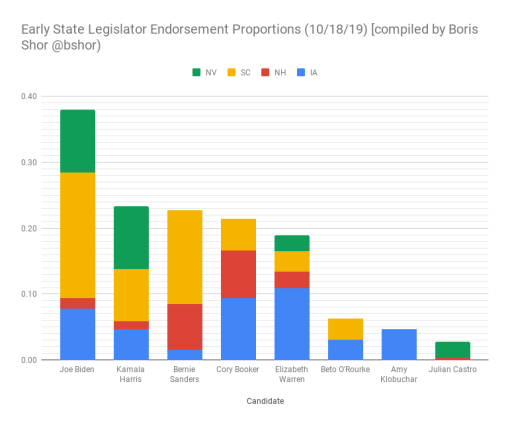

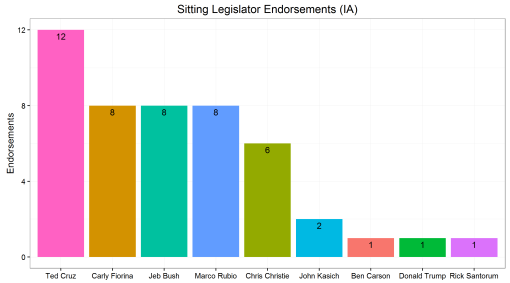

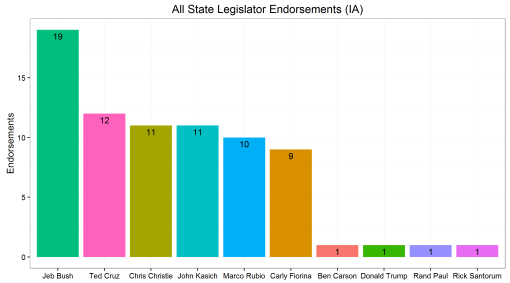

Now let’s turn to the four early states, where 178 of 374 possible endorsements of active candidates have been made (48%). Here, I’ve transformed the raw endorsement counts into proportions of in-state Democratic endorsements to account for the very different sizes of numbers of available Democrats across the states. Biden has the lead, but Warren and Klobuchar are doing fairly well. Sanders is further behind, and Buttigieg is nowhere.

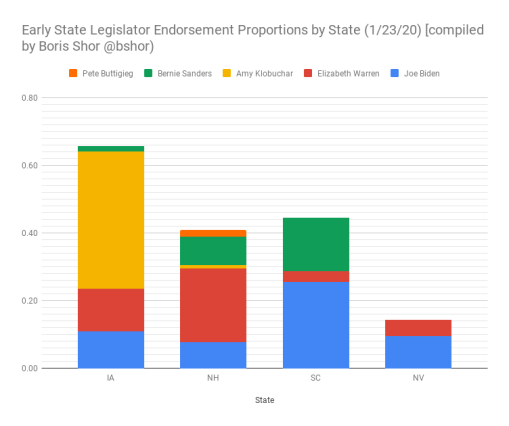

Alternatively we can plot out the early states. Here, we see that the vast majority of Iowa’s Democrats have already made a choice, and it is disproportionally for Klobuchar. New Hampshire is an area of strength for Warren, while South Carolina and Nevada are Biden’s strengths.

Alternatively we can plot out the early states. Here, we see that the vast majority of Iowa’s Democrats have already made a choice, and it is disproportionally for Klobuchar. New Hampshire is an area of strength for Warren, while South Carolina and Nevada are Biden’s strengths.

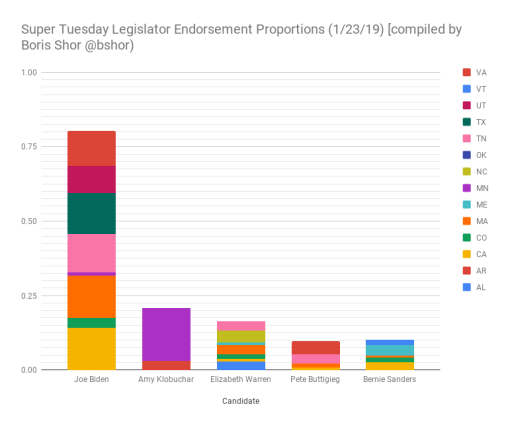

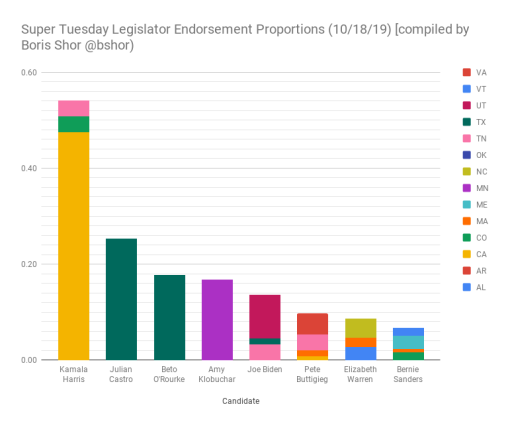

Finally, we can look at the 14 states holding a primary election on Super Tuesday 2020. We’ve only had 119 endorsements out of the maximum possible of 1,057 (11%). Joe Biden absolutely dominates here, with solid endorsement numbers from 6 states. The other candidates are barely competitive.

I haven’t finished the ideological breakdown of these endorsers, but I hope to do so soon (and will update the post when I do).